Print Money, Buy Time

Fiat currencies have short shelf lives.

Many people believe that US President Richard Nixon ended the gold standard in his famous speech on August 15, 1971.

Not quite true.

The Nixon shock was the final step of a 49-year process that removed gold from the financial system. It also created an unstable "non-system" built on promises that cannot and will not be kept.

"The sinews of war are infinite money" —Marcus Tullius Cicero

Europe’s biggest economies were close to collapse after sleepwalking into World War 1.

Their leaders — as is the custom — bankrupted their nations to murder their neighbours. Between 1914 and 1918, they got 20 million people killed and wasted vast resources.

And war is expensive …

Before World War 1, Britain ruled a vast empire and their pound sterling was the world’s reserve currency.

Despite winning, Britain emerged from the war deep in debt — mainly to the United States — as their gold reserves were not enough to fund the war.

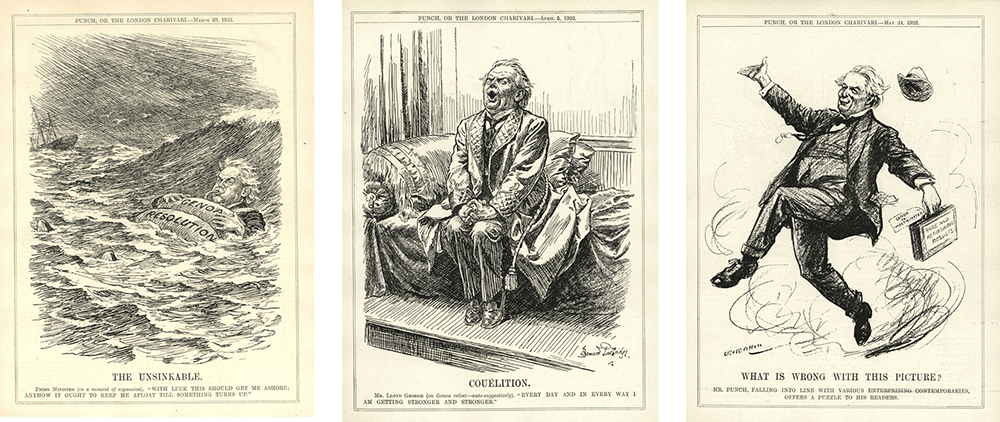

Developed world economies had been on the classical gold standard since the 1870s. This system had one basic rule:

- A banknote issued by a national central bank promised a specific weight of gold.

The gold standard also had one serious flaw:

- The price of gold was fixed … And economics 101 tells us that prices decided by officials or committees are almost always wrong.

A fixed gold price also meant that a nation's money supply depended on the amount of metal dug from the ground, or earned in international trade.

Say hallo to ‘paper gold’

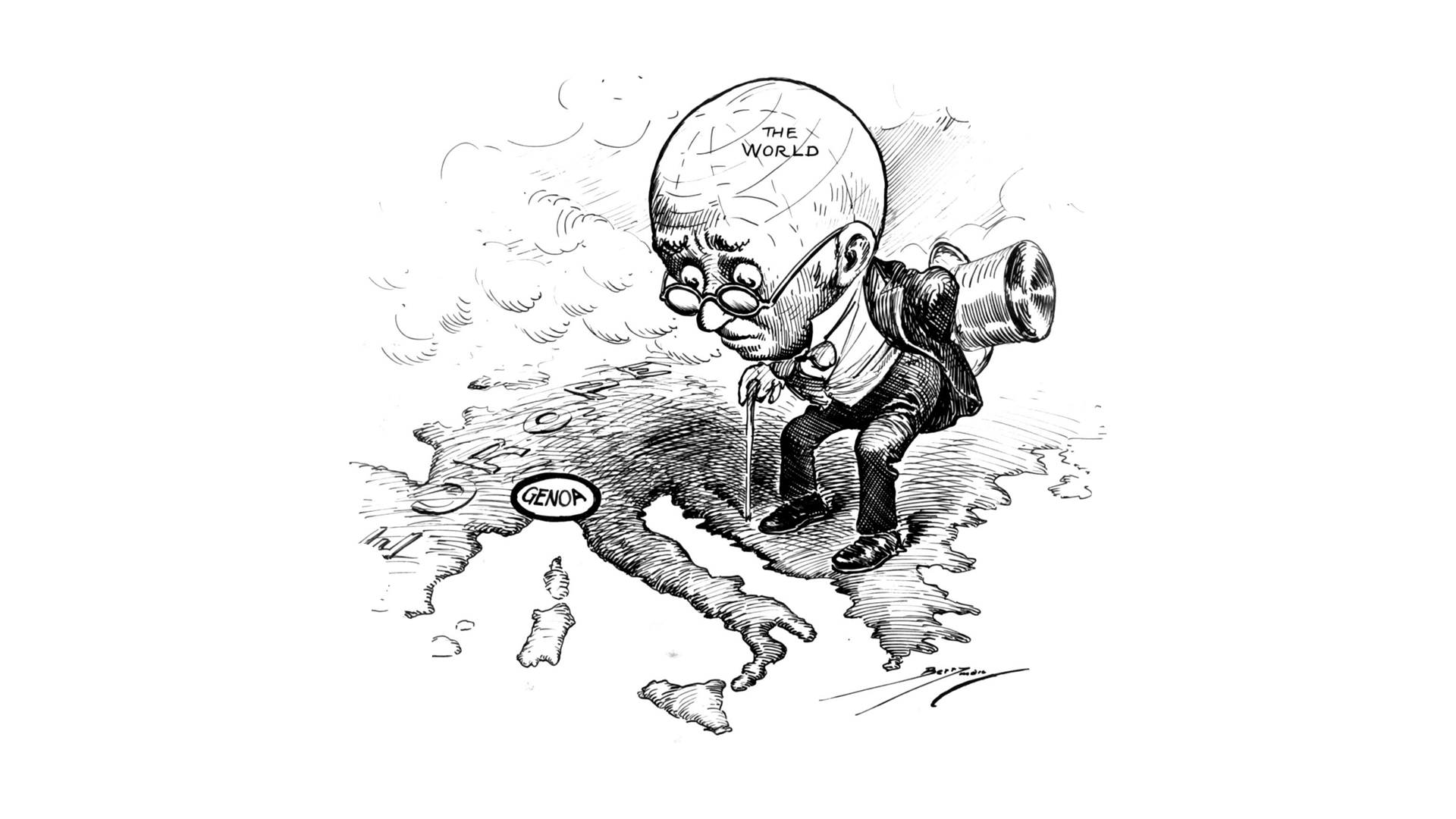

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George wanted Britain to remain dominant, despite the country being skint.

So he convened the Genoa Economic and Financial Conference in April 1922 (FOFOA's excellent overview here). The leaders of 29 nations and 5 British dominions gathered at the Palazzo San Giorgio, to plan a new international monetary system.

Behind closed doors, the British and American governments pressured the others, until eventually, Lloyd George got what he wanted.

At the end of the conference, a new global monetary system was announced: the Gold Exchange Standard. For the first time, major banks could accept US dollars and British pounds as reserves — alongside physical gold.

- Reserves, basically, are governments, banks, and major institutions' savings. Nowadays, reserves also include foreign currencies, government debt, and other financial instruments.

This was the birth of the concept of a "reserve currency" which is obviously a contradiction in terms.

Before 1922, precious metals were the only trusted assets. After Genoa, the world was told that paper promises issued in New York and London were just as good.

But there are differences:

- Physical gold was created in finite amounts by nature or God or whatever is out there. It is expensive and difficult to find, mine, refine, and store.

- Governments and banks could create dollars and pounds — at a very low cost and without limit.

The result was that the US and UK could print a good chunk of their reserves, while the rest of the world had to earn theirs — by creating and selling real goods and services.

Under the classical gold standard, trade imbalances between nations were settled with shipments of physical gold. Without any balancing function, the stage was set for the UK and the US to run ever-growing deficits “without tears" in the decades that followed.

This was a fantastic deal for the currency issuers — at first, but gradually brought de-industrialization and a declining ability to produce things of value. But that's a tale for another day.

The Age of Inflation

The new system was also fundamentally unstable, and the root cause is simple:

- Before 1922 the world’s financial system was based on ownership of gold.

- After 1922, the financial system was also based on promises of gold.

You have probably noticed that it is easier to make promises than to keep them. And governments are just as unreliable as everyone else: A 2013 study showed that governments keep only 50—80% of their financial promises.

(I don't know if this stat is true. I asked ChatGPT for examples and that's what I got, but it couldn't provide a source. )

Close calls and quick fixes

Because humans often don't keep their promises, a financial system based on those promises will often blow up. These promises are also known as credit or debt. And every decade or two, we have a financial crisis that needs government intervention to prevent collapse.

Here are some big events that got us here:

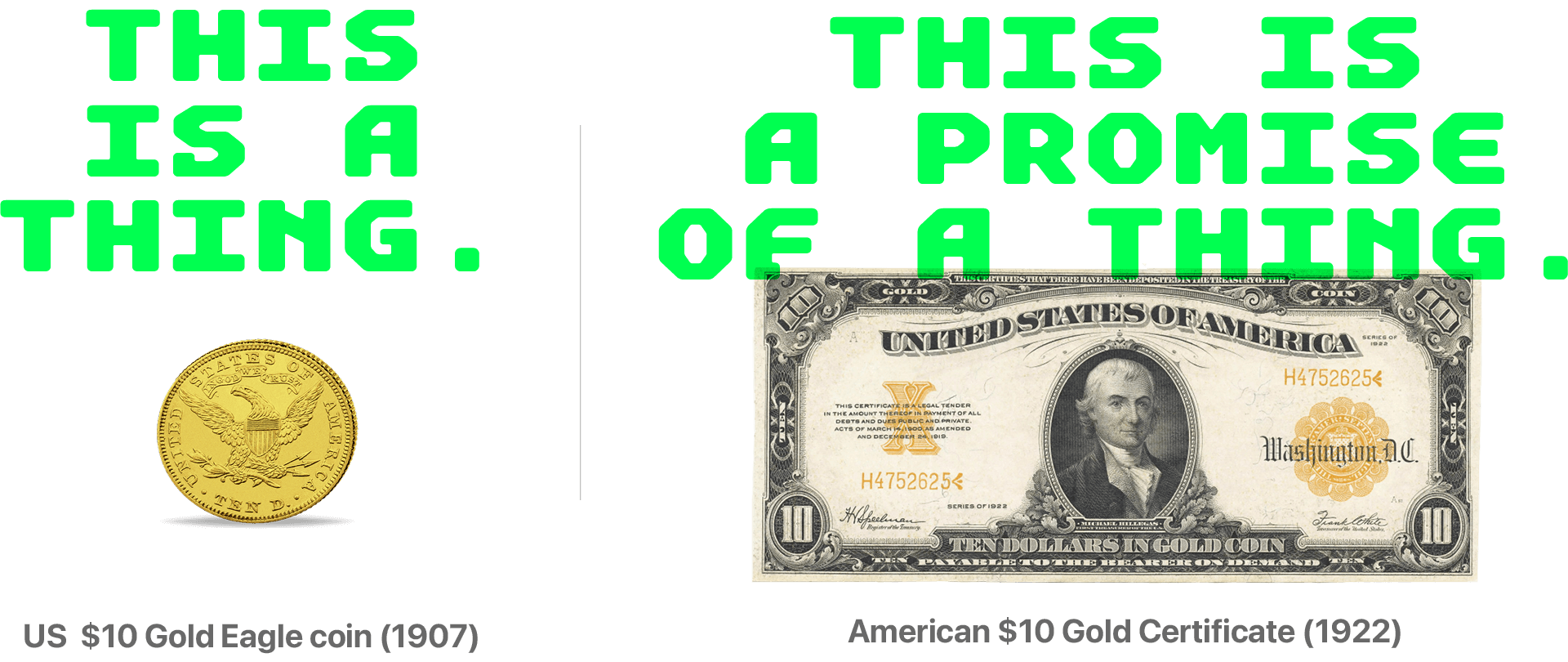

1933 — Executive Order 6102

- President Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated while the US was deep in the Great Depression.

To stimulate the economy, FDR decreed that the dollar be devalued by 70% against gold. He also ordered the confiscation of all 'gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates' held by American citizens. These measures successfully inflated away much of America's debt.

1944 — The Bretton Woods Conference

- As World War 2 ended, the leading nations gathered at Bretton Woods for another conference. And again, the winners of a world war designed the world's new monetary system.

Britain was even weaker than at the end of WW1, so the US delegation imposed their preferred solution on the world. The resulting agreement pegged foreign currencies to the US dollar — which alone was convertible to gold — at a fixed price of $35 an ounce.

This, officially, made the US dollar as 'good as gold',

But Bretton Woods was another flawed system and the rise of America's consumer society doomed it to failure. Again, the reason was simple:

- The dollar was still a promise of gold to foreigners, so when the US imported more than it exported, the difference had to be settled by shipping physical gold abroad.

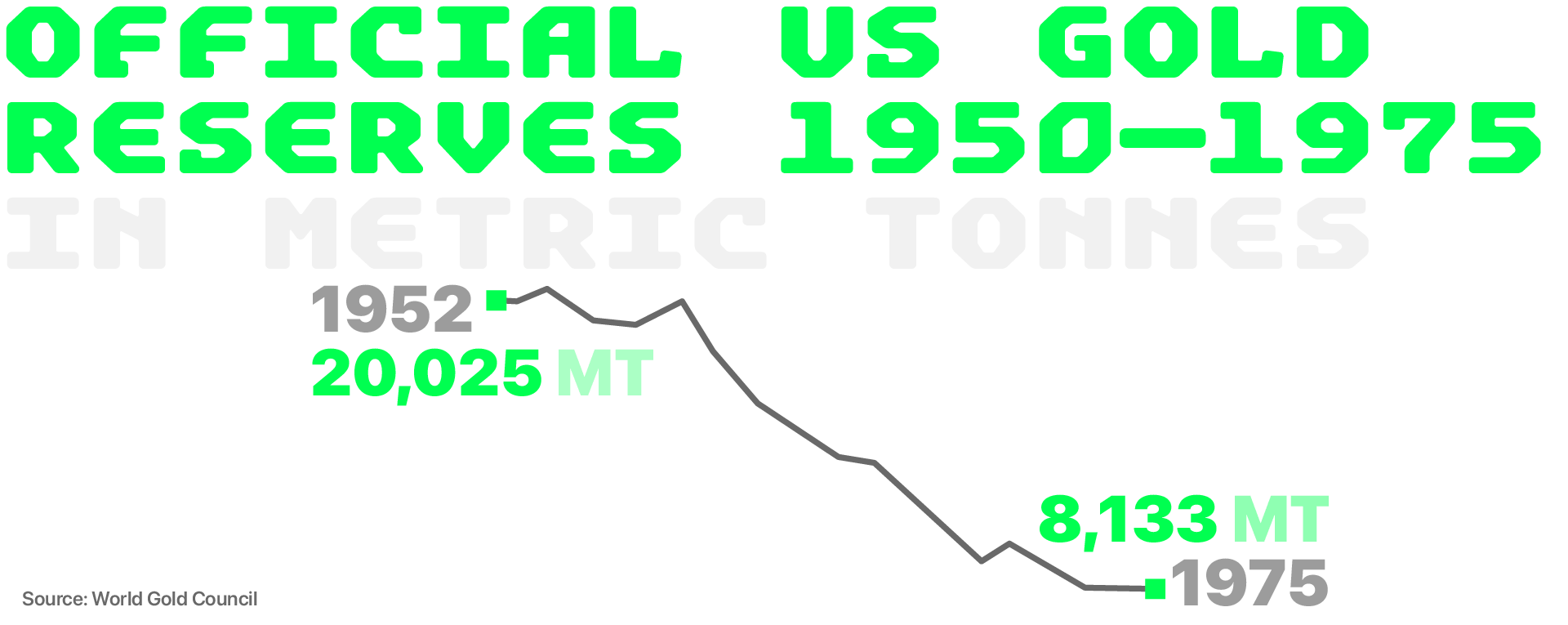

The more Americans consumed, the more gold was lost. And from the 1950s the US Treasury's gold holdings fell to 8,133 tonnes. This required serious action:

1961 — 1968: The London Gold Pool

- The London Gold Pool was a secret agreement between eight central banks: Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the US, the UK, and West Germany.

The central banks pooled their gold reserves, and covertly traded to defend the $35 per ounce gold price. The scheme collapsed in 1968 after word got out, and markets tested participants' willingness to support the dollar.

1971 — The Nixon Shock

- A new version of the global monetary system was born on August 15th, 1971. US President Nixon went on TV to finally sever the link between gold and the dollar — ending the Bretton Woods system.

The Nixon Shock was a sudden political decision made without warning or consultation abroad.

Nixon said he was protecting the dollar from foreign ‘money speculators’. But these speculators were fiction — invented to disguise the government's refusal to pay its debts.

The move led to ongoing currency volatility, a 65% dollar devaluation through the 1970s, and the gold price reaching record highs.

After all that, the 49-year process of removing gold from the core of the financial system was complete, and the dollar famously became "our currency and your problem".

This left the Nixon government with a new challenge: why would foreigners want dollars, if dollars no longer promised gold?

The solution they found was genius:

1998 — Long-Term Capital Management

- When a hedge fund called Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) blew up, it almost took down the global financial system.

The world was largely unaware of this near-miss, which needed a bailout organized by the US Federal Reserve. You might not have heard of this crisis, but it certainly shook Eddie George, Governor of the Bank of England at the time:

We looked into the abyss if the gold price rose. A further rise would have taken down one or several trading houses, which might have taken down all the rest in their wake. Therefore at any price, at any cost, the central banks had to quell the gold price, manage it. It was very difficult to get the gold price under control but we have now succeeded.

In the aftermath of the LTCM crisis, the Bank of England sold 55% of its gold reserves, pushing prices to 20-year lows.

The decision to sell off so much gold at such low prices is ridiculed as "Brown's Bottom" after Gordon Brown, then Chancellor of the Exchequer of the UK. But Britain's sacrifice kept the US-dollar-based global currency system going for another few decades.

Too much money

There was also the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, plus too many other accidents, secret deals, and swindles to go into here.

This quick tour through history illustrates the instability that followed cutting the monetary system off from (physical) reality.

Under constant political pressure, currencies have undergone a total transformation, and now it takes some detective work to understand what a dollar or a euro or a pound actually promises.

The answer is 'not much'. That would be fine if central banks could keep their promise of 'price stability' – but ongoing superinflation is exactly how they fail.

CTRL + P

Now, we have a mostly intangible financial system where digital currency is typed into existence when commercial banks make loans.

And that means 92% of the world's currency does not physically exist — residing as bits and bytes on digital ledgers on bank server farms.

As there are no physical constraints on money creation, the only limits are political, which means no limits at all. And in times of crisis, politicians solve problems by kicking debt into the future by printing more money:

- 2008 financial crisis? Print more money and give it to banks. Covid-19? Print more money and give it to the pharma industry. War in Ukraine? Print more money. Energy crisis caused by sanctions? Print more money. Climate change? Print more money …

When currency is printed to solve everyone's problems, the currency itself becomes the problem. And this makes the ability of Western governments to keep any kind of promise very shaky indeed …

The end of paper gold?

It is 101 years since the Genoa Conference created an unstable monetary system that requires endless duct-tape to prevent collapse. But is there a solution in sight?

On January 1st this year, the Basel III Accord came into effect.

This is a set of international banking rules designed to stabilize international banking.

- Basel III reclassifies physical gold as a Tier 1 asset.

It also creates a framework to end the domination of paper gold, and related derivatives. The demotion of paper gold could also undo the mechanisms introduced in Genoa.

Of course, most people cannot care about arcane changes in international banking law. But the point is that for 101 years, major changes to the monetary system have been:

- Negotiated behind closed doors at international conferences (1922 and 1944).

- Announced after decisions made in private by a handful of people from one nation (1933 and 1971).

- Secret deals that few understood until a long time afterward (1961–68 and 1998).

Does this pattern predict the future?

You weren't asked about Genoa or Bretton Woods or the Gold Pool or TARP or the Troika or Reverse Repos or any of the other measures to keep the wheels from coming off.

The Superbubble view is that we can expect something similar soon, but with very different sets of winners and losers.

There are many possible triggers, actors, and outcomes, so I'll be tracking it, right here.

x C x